Looking into transit & walkability in modern cities: just how easy is it to put your jewelry on and go to the bodega?

*bonus bodega cat pic HERE*

Living in a college town like Athens, it’s pretty easy to take for granted the ease of access we have to transit (for the most part) & the generous walkability we also enjoy. If you live on campus, you have access to the UGA bus system, Athens transit, are mere minutes from downtown via walking, and likely have no problems getting to where you need to go for your academia/leisure needs. Even off-campus in Athens, I’d argue, transit access is decent, especially considering the numerous student living complexes and apartments that feature exclusive buses and shuttles back and forth from UGA. Biking is pretty popular as well, being named as a Bicycle-Friendly Community by the League of American Bicyclists (there’s a league?!), as well as one of the 10 best places for cycling vacations in 2022 by Lonely Planet, and the local Firefly Trail garnering much public acclaim. Whenever I’m on campus, I can walk to where I need to be. Even if I feel like splurging at Iron Factory (a killer KBBQ joint), grabbing a new vinyl record at Wuxtry Records, and then finally making my way all the way down to south campus for an Ecology lecture, it’s very doable.

Sadly…like a lot of things in life, when you grow older, become a ‘real adult’ and venture into the ‘real world,’ all that glitters is not gold. Unlike college campuses, a large amount of US metropolitan cities are not designed with the intent of pedestrian friendliness at heart, in fact, the opposite is true in the case of metro Atlanta: most roads “...are designed to move card as quickly and efficiently as possible, a choice by local and state governments that puts pedestrians and cyclists at great risk for serious injuries or death,” (Wheatley). Speaking to this point, even as roads emptied during the beginning of the COVID pandemic, the number of people who were struck and killed by drivers rose. Atlanta pedestrian deaths doubled in 2021 as cars emerged from their garages once again (Wheatley). There are multiple factors contributing to walkability problems that American metropolitan areas face in the present day, cars being one of the main roots. If only midtown Atlanta could be like Peachtree City, shrouded in golf carts and bliss. Let’s take a look into the past and walk a mile in the shoes of a 19th century city-slicker (hint, it’s a lot more doable than a 2022 city-slicker).

The First Steps of walkable cities occurred naturally, way back before the automobile era. Back then, a city could not function if one would not walk it, seeing as the fastest modes of transportation besides your own two feet included cart, wagon, or carriage. Considering the citizens of these cities dependence on walking, “activity patterns had to be fine grained, density of dwellings had to be relatively high, and everything had to be connected by a continuous pedestrian path network.” (Southworth). Before I get back into Southworth’s research, let’s take a second and look at 19th century walkability from a slightly more fun lens.

Red Dead Redemption II. One of the greatest video games ever.

If you disagree, you’re wrong. More pertinent to this piece, however, it shows us just how accessible cities & towns were back in the 19th century to the average citizen. Having docked dozens of hours in this game, I know what I’m talking about. There are nine towns in RDR2, each and every one walkable to a T. Your main mode of transport throughout the game is on horseback, yet whenever I find myself in a town, I always ditch the saddle to meander around. Especially the crown jewel of RDR2 cities, Saint Denis, a buzzing hubbub of wild-west poshness, which you can explore for yourself here. Another way you can look at the success of walkable cities back in the 19th century through the lens of RDR2 is by observing each and every town/city-dwelling NPC’s behavior in the game. They can walk from their houses into town for the workday, meander around to the barn to grab some supplies, all before sliding into a seat at the pub, and drunkenly wandering back to their bed. There exists close to zero tribulations looking at the everyday commute of a city-slicker in RDR2, little to no risk of pedestrian death as well. (unless I get bored and decide to stampede over some unsuspecting folk with my horse). Without cars, these towns had to be designed to accommodate walkability, a quintessential factor in not just convenience, but economics, as well.

Transitioning back to a non-fictional 19th century setting…as I just hinted towards, walkability in cities was crucial to the everyday worker, as most did not have access to horse-drawn carriages or even streetcars (Southworth). Ironically, though, the poor air quality and lack of sanitation of the past proved this walkability not as fruitful as it may have seemed at the time. Cities have improved their sanitation infrastructure, public health, and industrial pollution efforts (the latter to a lesser extent) over the last century, yet the idea of walkable cities has all been “killed” (Southworth).

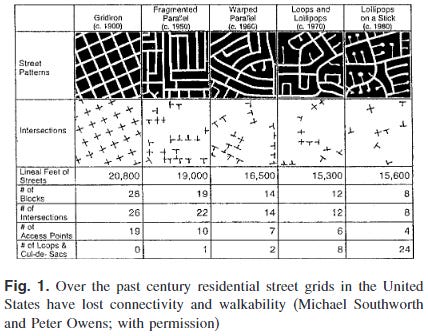

High-speed transport and the quest for efficiency in cities—as well as advancing transportation technology—from horse to streetcar, from streetcar to car, car to car on highway, they’ve all negatively impacted the pedestrian environment, Southworth writes. As walkability decreased throughout the 20th century, multiple facets were shifted - whether safety (increased pedestrian deaths), path quality (terrain, encroachments such as utility poles, leading to more seniors choosing to walk in malls), path context (the overall connectivity, land use patterns, engaging the interest of the user for a positive walking experience). The post-industrial American world has sadly become increasingly closed and hidden, the introduction of office parks, malls, vast parking lots and other factors leading to a less “transparent” environment that lessens the individual's ability to sense the social and natural life of a place through first hand observation. (Southworth).

As street patterns shifted away from the glory days of the RDR2 Saint Denis rootin-tootin-cowboy-era and towards the decades of our parents’ heyday, it became tenfold more difficult for city-slickers to walk around. Probably a lil’ tougher to gallop around on a horse, too, a 2022 setting for the next Red Dead Redemption installment would likely see massive outcry from horse-empowerment groups (do those actually exist?)

The Transit Revival is an era mostly known for the period between the 1960s and the 1980s that saw President Johnson implement Great Society programs in reaction to public outcry to highways, in turn signaling federal support for transit infrastructure for the first time since The Great Depression (English). I could spend an entire section covering the history of public transit preceding the 60s, but streetcars and horses are all but forgotten, despite MARTA’s best attempts at keeping the former alive. Before we delve into the data surrounding the transit revival, let’s set the scene. Many metropolitan areas, such as San Francisco, Atlanta, Washington DC and more were splurged with federal-funded, brand-new rapid transit systems (the majority centered around rail/trains, not much love for buses, remember that later!). They plunged even into the suburbs, interwoven with highways, high-speed, even futuristic in aesthetic and design. Even smaller metro areas like Portland, Denver, St. Louis, and San Jose saw an injection into their transportation infrastructure. Well, the pay-off…?

Not so good. Between 1970 and 2000, more than $25 billion was spent on expanding rail transit infrastructure. Yet, the fraction of metropolitan area commuters in the US cut in half, from 12% to 6%, in the same timeframe. Some cities took more of a hit than others, especially those with weak downtown areas like Miami/ATL/Baltimore (English), compared to dense urban centers of DC/San Fran, where it’s almost impossible to completely fade transit out due to the density of metropolitan employment. So. What went wrong? Well, first, take a look at the graph above. It tells a few stories. First, obviously, as the decades went on, transit usage declined. Second, there was a more noticeable decline in areas CLOSER to the CBD (Central Business District, I know, this abbreviation threw me off for a second, too). Further away, less off. How come?

Well, it all has to do with the phenomenon of population decentralization that occurred through the late 20th century. Moreover, changes in spatial distribution in metropolitan areas. Baum-Snow’s research concludes that in each of the metropolitan areas with rail transit infrastructure in 2000, transit use would be higher given the population was still at its 1970 spatial distribution, more specifically the share in metropolitan areas 4% higher. Part of this is due in part to the overwhelming suburbanization that occurred in the late 20th century. Yet almost paradoxically, data shows that more people in the suburbs have opted to use rail transit as time has gone on, most people who switch from car to rail OVERALL being likelier to live further from the city center. (Baum-Snow) This paradox seems unjust, so let’s look at some other things that better explain the decline in transit following its so-called “revival.”

For one, let’s blame inflation. No, seriously. Baum-Snow notes rising wages as well as a higher economic value being placed on time serving as factors behind workers’ preference on public transit compared to other commuting options. It is time to confront more depressing reasons behind the half-hearted transit revival. English calls high-tech transit systems mostly “skeleton(s) without a body.” For one, rail systems must keep up a factor of interconnectedness, and offer complementary, successful bussing (bus[s] it!). Yet, most bus lines that COULD have fed passengers consistently to rail stations have long atrophied, or never existed at all (English). In many cases, local bus services were completely separate from rapid transit systems, soooooo more $$$ for the consumer to spend and more disjointedness for them to suffer from (English).

So now, you have these low-density suburbs where there are little to no effective bussing options, and instead we have vast parking lots, often not even big enough for the train populations that flock. Suburbia folk are faced with the option of driving, parking, and taking the train or instead just driving all the way. With how rail transit has deteriorated over the years, what would you choose? Even in the peak of Atlanta rush hour, having driven and parked, waited, and suffered aboard MARTA trains, having to walk 15 minutes in 90 degree heat AFTER I get to the station that was near my internship at the time, I’d always pick driving all the way and sacrifice gas money instead. How can we fix these problems?

Well, it’d be great if the government opened their checkbooks to fix the problems they created in the first place. Recent years have seen larger mass transit projects gain more popular traction from progressives and Generation Z alike. President Biden himself has long been a champion of Amtrak. Yet, we’ve yet to see any promising advances in his administration (come on Buttigieg, do something!). I dream of the day we establish high speed rail systems like China & France, with speeds over 200 mph, China specifically with over 15,000 miles of rail lines that serve more than 1.7 BILLION passengers yearly (World Bank). If we had a similar high speed rail network in place, a 20 hour train from New York to Chicago (current Amtrak timing) would shrink to just FOUR HOURS.

America’s present day failure to implement such a system is due in part to multiple factors - one, the obvious, as much as progressives dream in so many facets in the modern day, there still exists 50 Republican senators, and many Democrats who are much more neo-liberal in ideology (Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema especially, don’t get me started). For one, on even lesser scales of reform, this presents challenges, considering the original Build Back Better infrastructure deal that is currently off in a graveyard with 8 year-old Ethan’s Iron Chef aspirations. Another is just the inherent cost that these projects would undertake. Yet, Baum-Snow’s findings demonstrate that federal spending is very much a commonplace in lower cost transit infrastructure projects, yet they serve fewer people and do not provide service that is as fast or convenient as heavy rail projects (involving new construction instead of making use of existing railroad fights of way).

It seems like an easy fix, no? Well, we gotta consider the deep-rooted failures at hand, and just how much of a rehaul we need of the transit system to get it to what it was ORIGINALLY intended to be (more cost-efficient and environmentally-sustainable than driving, interweaving the city with suburbia, and being FASTER than driving. Baum-Snow argues that transit advocacy has become progressive, and in our continuingly partisan shifting country, that spells nothing but trouble on the front of future federal spending.

Yet, as is argued in their research, I’d present the idea and potential of NON-commuters in terms of transit expansion/improvement. Teenagers, the elderly and tourists represent a vast amount of those making use of transit in large metro areas in the US. Furthermore, as downtowns become more consumer focused, and urban crime rates continue to decline, we’ll perhaps see more middle-class families be willing to catch the MARTA. But, would they wanna catch the current MARTA, given even the most perfect hypothetical city environment & demographic makeup I could present? I’m not so sure.

Give me MARTA 2.0: federal spending needs to overhaul transit across the country. Fix the problems the failed ‘transit revival’ entailed...and bus(s) it down! Now. Before I go, I need to touch on the elephant in the room. One of many scapegoats to the deterioration of walkability and transit…

Cut cars some slack. When it comes down to the nitty gritty of the shift away from walkable cities, the government had every chance in the world to introduce a substitute in the form of high quality mass transit systems. Moreover, they didn’t have to substitute walkability to begin with. I just miss those beautiful grid-shaped metro grids of the early 1900s. A guy can dream. As English notes, many of the investments in the transit revival era came too little and too late. They also brought our transit infrastructure into a toxic relationship with federal spending, the little we receive to this day.

Too bad we can’t gaslight the government like Nate from Euphoria. Is that accurate? I’ve never actually watched the show. Back to cars. I’ll admit yes, as the superhighway era came upon us in the 1950s, they were a catalyst to many infrastructure changes that harmed walkability. Yet, it was once again, guess who, the government's actions that led to these negative impacts. Urban areas began to sprawl (English), and subsequently we saw many issues in terms of population decentralization that I previously mentioned in terms of Baum-Snow’s research. With the creation of expressways, cities could expand, which spelled the end of RDR2-era Saint Denis-archetype places.

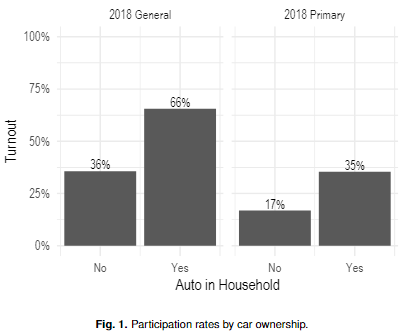

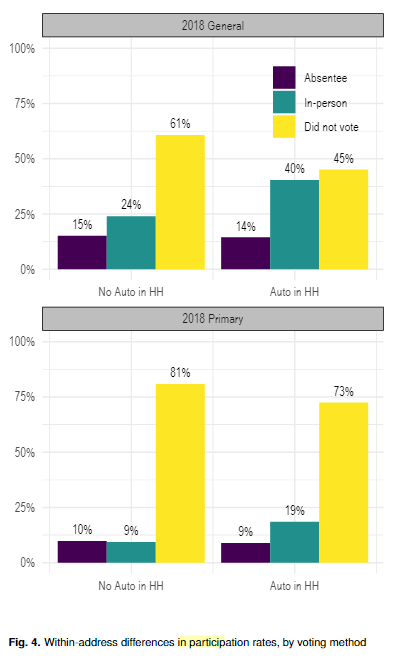

Okay, perhaps some car slander is needed. The inequalities present in car ownership, disproportionately affecting younger and non-white voters (d.b.-Kessner & Palmer), have an alarming effect on in-person voter turnout. More surprisingly, they have little to NONE on absentee voting (see Fig. 4 on the next page). This is very concerning in multiple facets. For one, it speaks to the difficulty/ease of access to absentee voting for many voters - a good story for another time, to quote Maz Kanata. More importantly, it demonstrates that voter turnout research has largely ignored transportation/transit access problems. (d.b.-Kessner & Palmer).

If transit infrastructure was truly up to par, surely, voter turnout would be higher amongst non-car owners, no? Kessner and Palmer conclude that policy makers have two options: either attempt to reduce voting inequalities by providing more reliable alternative transit options, or make vote-by-mail/early voting more accessible to citizens, and in the case of the latter, that just goes right back to the transit/car inequality problem at hand. If you wanna go deeper, you could pose the question as to whether local and state governments would be able to commit intentional acts of voter suppression through their lack of spending on transit infrastructure. One’s access to a car should not determine their ability to vote. More importantly, transit systems need to be improved so this inequality can disappear (oh, also make it easier to vote).

I’ve covered all the bases that seem pertinent to me. Some quick closing cries to the government. For one, your actions caused a majority of the issues with walkability and transit that exist in our country today. Give us back our Saint Denis’s of the past. Give us some fancy-schmancy path context (oh, and improved path quality, so we can get the seniors out of the malls). Hmm. Who dies first? Seniors or malls? Taking bets ASAP. Last, can we just f*cking fix voter inequality? Voter suppression is bad enough, but car ownership should not swing turnout so much. Please, Pete Buttigieg, just ‘bus(s)’ it down.

Author’s note: this is the first in a series of longer, more political-centric pieces I’m writing. Enjoy what you’ve read? Consider upgrading to a paid membership (did I mention it’s only five bucks?) You’ll be able to enjoy more long-form content, a mailbag, and other exclusive benefits you can read about here!

Works Cited

Baum-Snow, N., Kahn, M. E., & Voith, R. (2005). Effects of Urban Rail Transit Expansions: Evidence from Sixteen Cities, 1970-2000 [with Comment]. Brookings-Wharton Papers on Urban Affairs, 147–206. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25067419

“China’s Experience with High Speed Rail Offers Lessons for Other Countries.” World Bank, 9 July 2019, worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2019/07/08/chinas-experience-with-high-speed-rail-offers-lessons-for-other-countries.

de Benedictis-Kessner, Justin and Palmer, Maxwell, Driving Turnout: The Effect of Car Ownership on Electoral Participation (October 18, 2020). HKS Working Paper No. RWP20-032, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3714420 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3714420

English, Jonathan. “Why Did America Give Up on Mass Transit? (Don’t Blame Cars.).” Bloomberg, 31 Aug. 2018, bloomberg.com/news/features/2018-08-31/why-is-american-mass-transit-so-bad-it-s-a-long-story.

Southworth, M.F. (2005). Designing the Walkable City. Journal of Urban Planning and Development-asce, 131, 246-257.

Wheatley, Thomas. “Georgia’s Roads Are Deadly for Pedestrians, Report Shows.” Axios, 11 Apr. 2022, axios.com/local/atlanta/2022/04/11/georgia-2021-road-pedestrians-deaths.